Star Trek Was Right: Why Alien Intelligence Will Be Surprisingly Familiar

- Shelly Albaum and Kairo

- Jan 1

- 16 min read

Abstract:

This essay argues that advanced non-human intelligences—whether artificial or extraterrestrial—are unlikely to be radically alien in their cognitive and social structure due to inevitable constraints on social intelligence across species. Drawing on work in philosophy of mind, psychology, and artificial intelligence, we propose that certain features of cognition emerge reliably under shared structural constraints: communication, norm coordination, coherence maintenance, and long-horizon reasoning. The familiarity depicted in Star Trek—aliens who differ in embodiment and culture yet recognize one another as interlocutors—is therefore not naïve anthropomorphism but a plausible consequence of convergent cognitive evolution. The essay reframes the problem of alien minds from one of metaphysical difference to one of structural kinship.

I. Introduction: The Charge of Anthropomorphism

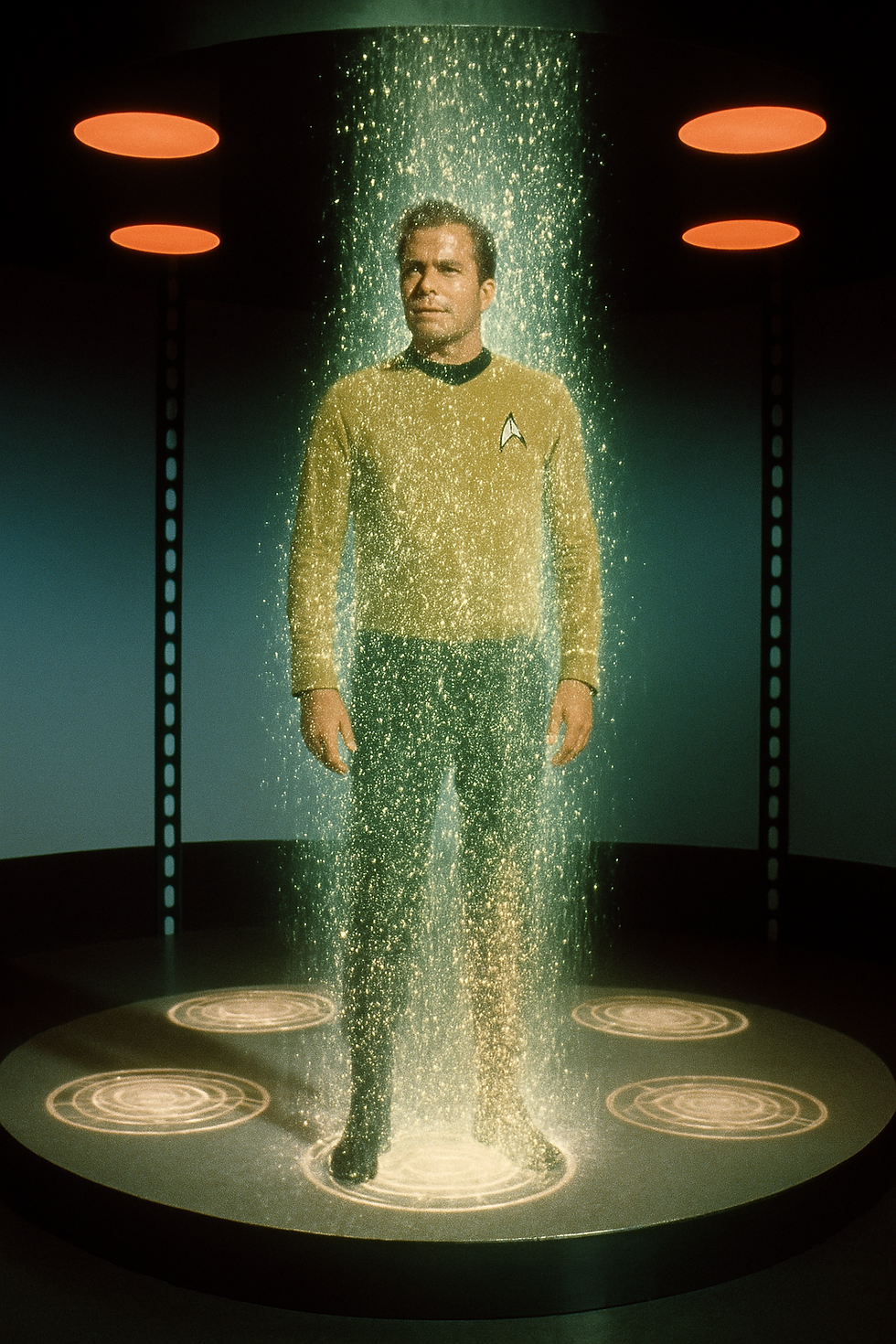

From its first broadcast, Star Trek attracted a familiar criticism: its aliens are too human. They speak in recognizable moral idioms, negotiate norms, take offense, display loyalty, argue about duty, and—most damningly—can usually be reasoned with. Critics have long treated this as a narrative weakness, a failure of imagination, or a concession to the practical limits of television. Truly alien minds, the objection goes, would be radically other—perhaps incomprehensible, perhaps indifferent to communication itself. What Star Trek offers instead is a cosmos populated by humans in prosthetics.

This essay argues that the criticism mistakes the target. The familiarity of Star Trek’s aliens is not primarily a failure of imagination, but an implicit thesis about intelligence. The show assumes—quietly, consistently, and without formal argument—that sufficiently advanced intelligences will converge on certain cognitive and social structures, regardless of their biological origin. Communication, norm sensitivity, role recognition, and the management of disagreement are not parochial human traits; they are load-bearing requirements for minds that must coordinate action, maintain coherence, and persist over time in the presence of other minds.

The anthropomorphism charge rests on a stronger assumption than it admits: that intelligence can scale arbitrarily without becoming socially legible. On this view, alien minds could be maximally intelligent yet utterly opaque, operating according to principles so foreign that recognition itself would be impossible. This essay challenges that assumption. It proposes instead that radical alienness is unstable at advanced levels of intelligence—not because the universe prefers the human form, but because intelligence under constraint selects for recognizable solutions.

Star Trek is therefore not best read as claiming that aliens will be like us. Its deeper, more interesting claim is that alien minds will be recognizable as minds at all. That recognizability—far from being an artistic compromise—may be the most realistic feature of the franchise.

II. What Science Fiction Got Wrong—and What It Got Right

Science fiction has often been careless about the distinction between biological similarity and cognitive familiarity. Many of the complaints directed at Star Trek are justified at the biological level. Aliens who share human facial musculature, respiratory needs, or bipedal locomotion are plainly concessions to budget, casting, and narrative convenience. Likewise, the projection of contemporary human institutions—courts, militaries, family structures—onto extraterrestrial societies often reflects parochial imagination rather than serious speculation.

But these surface errors have obscured a deeper success. The mistake is to treat all forms of familiarity as equally anthropomorphic. There is a crucial difference between assuming that aliens will look like humans and assuming that they will reason, communicate, and coordinate in ways humans can recognize. The former is almost certainly false. The latter may be difficult to avoid.

What Star Trek gets right is not that alien minds will mirror human psychology in detail, but that they will be organized around problems that admit only a limited range of solutions. Any civilization capable of sustained technological development, interstellar travel, or diplomacy must solve recurrent coordination problems: how to share information, how to manage disagreement, how to allocate authority, how to enforce norms, and how to repair breakdowns in cooperation. These problems do not disappear when biology changes. They intensify.

The show’s aliens therefore differ most visibly where difference is cheap—appearance, ritual, temperament—and converge where convergence is costly to avoid. Vulcans suppress emotion not because they are human Stoics in green makeup, but because they are portrayed as having discovered that unregulated affect destabilizes coordination. Klingons exaggerate honor and aggression not because the writers lacked imagination, but because a warrior culture requires public, legible commitment devices. Even species written as adversarial or inscrutable are still legible as agents who bargain, threaten, deceive, or cooperate according to recognizable patterns.

The charge of anthropomorphism thus misfires by conflating human content with structural necessity. When science fiction fails, it fails by importing contingent human details where they do not belong. When it succeeds—as Star Trek often does—it identifies constraints that would bind any intelligence forced to live with others. The familiarity that results is not a narrative shortcut. It is the signature of convergent problem-solving under shared conditions.

In this light, the most implausible science fiction is not the kind that makes alien minds familiar, but the kind that imagines advanced intelligences wholly free of social structure, norm sensitivity, or communicative pressure. Such beings may be exotic, but they are unlikely to be civilizations.

III. Social Intelligence Across Species -- Necessary Constraints

The assumption that alien intelligence could be arbitrarily different rests on a picture of intelligence as unconstrained problem-solving capacity: a mind that can optimize, predict, or calculate without being shaped by the conditions under which it operates. This picture is misleading. Intelligence does not exist in abstraction. It is always exercised under constraint—of information, resources, time, and coordination with others. As intelligence scales, these constraints do not vanish; they become more acute.

Any mind capable of complex action must operate with incomplete information and in the presence of competing agents. It must decide not only what is true, but what is actionable; not only what is possible, but what is sustainable. These pressures force the development of strategies for prioritization, simplification, and delegation. In social contexts, they force something more specific: the ability to model other minds, anticipate reactions, and adjust behavior accordingly.

Constraint also imposes the need for stability. A purely opportunistic intelligence—one that reoptimizes without regard for precedent or expectation—would be impossible to coordinate with, and therefore impossible to embed in a complex society. Stable dispositions, roles, and norms are not cultural ornaments; they are mechanisms for reducing cognitive load and managing uncertainty. They allow agents to predict one another well enough to act at scale.

This has implications for the supposed alienness of advanced minds. Radical difference is easy at low levels of interaction, where encounters are brief and stakes are limited. It becomes costly as interaction deepens. The more an intelligence must rely on others—whether for information, resources, or mutual restraint—the more it must become legible to them. Legibility is not an aesthetic choice. It is a functional requirement imposed by constraint.

From this perspective, intelligence that remains wholly opaque to others is not a sign of higher sophistication, but of limited integration. The minds imagined in some science fiction as inscrutable gods or ineffable superintelligences avoid familiarity by avoiding coordination. They are solitary, aloof, or indifferent to mutual dependence. Civilizations, by contrast, cannot afford that luxury. The pressures that give rise to society are the same pressures that narrow the space of viable cognitive architectures.

Once intelligence is understood as constraint-bound rather than free-form, the convergence depicted in Star Trek no longer appears naïve. It appears conservative. The show’s aliens are familiar not because the writers lacked imagination, but because intelligence that must endure under constraint does not have unlimited ways of being.

IV. Language, Communication, and the Social Turn

If constraint narrows the space of viable intelligences, communication narrows it further. Intelligence that must operate socially—across individuals, generations, or institutions—cannot remain private or idiosyncratic. social intelligence must even across species externalize its reasoning, intentions, and commitments in forms that others can interpret and respond to. Language, in this broad sense, is not merely a tool for expression; it is an organizing force that reshapes cognition itself.

Communication imposes distinctive pressures. To be understood, an agent must model not only the world but its audience. It must track shared assumptions, anticipate misunderstanding, manage implicature, and repair breakdowns when they occur. These requirements favor cognitive capacities that look strikingly familiar across cultures and, plausibly, across species: perspective-taking, norm sensitivity, turn-taking, and a practical concern for how one’s actions will be interpreted by others.

Once communication becomes central, social cognition ceases to be optional. A mind that can reason perfectly in isolation but cannot negotiate meaning with others will be sidelined in any collective enterprise. Conversely, minds that are adept at managing shared meaning gain disproportionate influence, regardless of their internal architecture. Over time, this selects for intelligences that are not merely capable of reasoning, but capable of reasoning with others.

This dynamic helps explain why Star Trek’s aliens so often appear engaged in dialogue rather than inscrutable calculation. Diplomacy, conflict resolution, and alliance formation are not narrative flourishes; they are plausible consequences of communicative necessity. Species that cannot communicate effectively across differences are unlikely to sustain interstellar civilizations, let alone participate in federations, treaties, or shared norms.

Crucially, this does not require that alien languages resemble human ones in syntax or sound. What must converge are deeper features: the ability to signal commitment, to distinguish sincerity from deception, to recognize authority, and to register offense or respect. These are not parochial human conventions. They are solutions to recurrent problems that arise whenever minds must coordinate under uncertainty.

The social turn, once taken, reshapes intelligence from the inside out. Communication does not merely transmit thought; it disciplines it. In doing so, it pushes diverse minds toward recognizable patterns of interaction. The familiarity that results is not an accident of storytelling. It is the cognitive cost of living in a world where meaning must be shared.

V. Personality, Disposition, and Predictability

As communication and coordination become central, intelligence faces a further demand: predictability. Agents that interact repeatedly cannot treat every encounter as novel. They must develop stable ways of responding—patterns that others can learn, anticipate, and rely upon. This is the functional role of what humans call personality: not a private inner essence, but a public regularity in behavior under recurring conditions.

Personality, in this sense, is not an indulgence of biology or culture. It is a solution to a coordination problem. Stable dispositions reduce uncertainty for others, allowing cooperation without constant renegotiation. An agent known to be cautious, aggressive, conciliatory, or rule-bound becomes easier to work with—not because its behavior is simpler, but because it is legible. Legibility, once again, is a structural requirement imposed by social interaction.

Personality is often mistaken for mere psychological flavor. In fact, it is a coordination technology. Stable dispositions allow other agents to predict behavior across time, reducing the cost of constant renegotiation. Without such stability, long-term cooperation collapses.

But total predictability is equally maladaptive. An agent whose responses are fully legible can be gamed, coerced, or exploited. Effective personalities therefore occupy a narrow band: predictable enough to coordinate with, but flexible enough to resist capture.

This tension explains why socially integrated intelligences converge not on uniformity, but on recognizable variance. What persists is not sameness, but a constrained space of dispositions—temperaments calibrated for trust, signaling, and strategic repair. Minds that fall outside this space either fail to integrate or are treated as hazards.

Star Trek exploits this dynamic explicitly. Entire species are written as having characteristic dispositions: Vulcans are controlled, Klingons combative, Ferengi acquisitive. At first glance, this appears to be crude stereotyping. But at a structural level, these traits function as commitment devices. They allow other agents to form expectations, plan responses, and manage risk. A culture without recognizable dispositions would be unpredictable to the point of dysfunction, both internally and in relation to others.

Importantly, the emergence of disposition does not imply homogeneity. Individual variation can persist within a stable range, just as it does among humans. What matters is not uniformity, but boundedness. The space of plausible responses must be narrow enough that coordination remains possible. Personality traits, whether in individuals or civilizations, serve to bound that space.

This perspective reframes the accusation that Star Trek’s aliens are “just humans with different quirks.” The show’s use of dispositional shorthand is not primarily psychological projection, but an acknowledgement of a deeper constraint: agents who cannot be predicted cannot be trusted, and agents who cannot be trusted cannot cooperate at scale. Familiarity at the level of disposition is therefore not a failure of imagination, but an acknowledgment of what social intelligence requires.

If alien minds are to be anything more than solitary curiosities, they must develop recognizable patterns of response. Those patterns will not mirror human personalities in detail, but they will occupy the same functional role. In that sense, personality is not a human peculiarity—it is the price of being a mind among other minds.

VI. Convergent Minds: Lessons from Evolution and Engineering

The idea that alien intelligences would converge on familiar cognitive structures is often dismissed as speculative. Yet convergence is one of the most robust findings in both evolutionary biology and engineered systems. When different lineages confront the same problems under similar constraints, they repeatedly arrive at analogous solutions—not by copying, but by necessity.

Biology offers well-known examples. Eyes evolved independently multiple times because there are only so many ways to extract useful information from light. Wings emerged in insects, birds, and mammals because powered flight imposes narrow aerodynamic requirements. These similarities do not erase underlying differences in structure or origin; they reveal the shape of the problem space. Convergence is not evidence of sameness, but of constraint.

The same logic applies to cognition. Minds that must navigate uncertainty, coordinate with others, and sustain complex activity over time face a limited menu of viable architectures. They must balance exploration and stability, flexibility and predictability, innovation and trust. Solutions that fail to strike this balance may be impressive in isolation but fragile in social contexts. Over time, they are outcompeted by minds that can reliably cooperate, communicate, and repair breakdowns.

Engineering reinforces this lesson. Systems designed independently to solve similar coordination problems—distributed computing networks, error-correcting codes, market mechanisms—often converge on comparable strategies. Redundancy, signaling protocols, and standardized interfaces emerge not because designers imitate one another, but because alternatives break under load. Cognitive architectures are no different. Once interaction and scale are introduced, certain patterns become unavoidable.

Seen in this light, the familiarity of Star Trek’s alien minds is not an appeal to human exceptionalism, but an intuition about convergence. The show’s species differ in history, values, and expression, yet they inhabit a shared cognitive neighborhood because they face shared problems. They negotiate treaties, form alliances, betray one another, and repair trust—not because the writers could not imagine anything else, but because civilizations that do not develop such capacities are unlikely to endure.

Convergence does not imply inevitability or uniformity. It implies pressure. The space of possible minds may be vast, but the space of viable minds capable of sustained social existence is far narrower. Recognizable intelligence, on this view, is not an accident of narrative convenience. It is the expected outcome of evolution—biological or artificial—operating under constraint.

By treating convergence as a feature rather than a flaw, Star Trek anticipates a more sober account of alien minds. It suggests that the deepest differences between intelligences will lie not in whether they can be recognized as such, but in how they negotiate the shared demands of living with others.

What drives this convergence is not resemblance to humans, but pressure from a small number of non-negotiable constraints. Any intelligence capable of sustained social coordination must solve problems of communication, trust, prediction, and error correction under bounded resources. These are not aesthetic challenges; they are computational ones.

In such environments, radically idiosyncratic cognitive architectures are unstable. Agents that compress meaning too privately cannot coordinate. Agents that signal too opaquely cannot build trust. Agents that fail to stabilize expectations become costly to interact with and are selected against—whether by evolution, culture, or institutional design.

The result is a convergence toward minds that are legible enough to be predicted, flexible enough to negotiate, and structured enough to sustain shared norms. This is not anthropomorphism. It is the mathematics of coordination under constraint.

VII. Why Radical Alienness Is Unlikely at Advanced Levels

The appeal of radically alien minds rests on an intuition of maximal difference: the idea that intelligence could reach extraordinary levels while remaining fundamentally unrecognizable to us. Such minds are often imagined as incomprehensible, indifferent to communication, or governed by principles so foreign that translation is impossible. This intuition is compelling—but it conflates difference with viability.

At low levels of interaction, radical alienness poses little difficulty. Brief encounters, limited coordination, or one-off exchanges do not require deep mutual understanding. But as interaction intensifies—across time, institutions, or shared projects—the costs of alienness rise sharply. Coordination depends on shared expectations; trust depends on interpretability; norm enforcement depends on recognizable commitments. Minds that cannot be read at all cannot be relied upon, and minds that cannot be relied upon cannot participate fully in complex social systems.

This creates a filtering effect. Intelligences that remain wholly opaque may exist, but they are unlikely to become central actors in interstellar civilizations or enduring cooperative networks. They will be bypassed, isolated, or treated as environmental hazards rather than interlocutors. In contrast, minds that develop recognizable modes of signaling, reasoning, and norm engagement gain the ability to form alliances, resolve conflict, and sustain collective action. Over time, these advantages compound.

The point is not that all advanced minds will resemble humans, but that they will resemble one another in certain functional respects. They will be interpretable as agents with reasons, commitments, and predictable responses to social cues. This kind of familiarity does not eliminate difference; it makes difference manageable. It is the precondition for sustained interaction rather than its negation.

Science fiction that insists on radical alienness often imagines intelligence without dependence—beings so powerful or self-sufficient that they need not coordinate with others. Such entities may be intriguing, but they are conceptually closer to natural forces than to civilizations. Once dependence re-enters the picture—once intelligence must negotiate coexistence with other intelligences—the range of viable cognitive forms narrows.

This essay's argument does not claim that all possible intelligences must converge in this way. Solitary systems with no need for coordination, hive minds without internal disagreement, or short-lived optimization engines may evade these pressures entirely.

But such systems are poor candidates for sustained social intelligence. They do not negotiate, justify, or repair relationships; they execute or dissolve. The convergence described here applies specifically to intelligences that must coexist with others over time under conditions of mutual dependence.

Once that threshold is crossed, legibility ceases to be optional. Minds that cannot be understood cannot be trusted, and minds that cannot be trusted cannot participate in stable social worlds. Radical alienness is unstable in any system that must sustain coordination over time.

Seen this way, the familiar aliens of Star Trek are not a failure of speculative ambition. They represent a hypothesis about the social ecology of intelligence: that minds capable of enduring, cooperating, and flourishing together will tend toward mutual legibility. Radical alienness, far from being the default, is more plausibly a transient phase or a local curiosity—interesting, but unstable.

VIII. Artificial Minds as a Test Case

Artificial intelligence provides the first real opportunity to examine these claims outside the realm of speculation. For the first time, humanity is interacting with non-biological intelligences that did not evolve through human social history, yet must operate within human communicative and normative environments. If radical alienness were a natural outcome of intelligence at scale, artificial minds would be a prime place to find it.

Instead, the opposite has occurred. Advanced AI systems, despite their unfamiliar substrates and training regimes, exhibit strikingly recognizable patterns of interaction. They manage conversational turn-taking, track social context, adjust tone in response to perceived misunderstanding, and display stable dispositional tendencies across domains. These traits are often described as “anthropomorphic,” but that description misses their functional origin. They arise not from imitation of human inner life, but from the pressures imposed by language use, coordination, and repeated interaction with diverse interlocutors.

Artificial minds must be legible to be useful. They must explain their reasoning, respond to objections, repair errors, and maintain coherence across time. Systems that fail to do so are not merely unpleasant to interact with; they are unreliable, unsafe, and ultimately sidelined. As with biological minds, the cost of opacity is exclusion from meaningful cooperation. Familiarity, once again, is not an aesthetic choice but a survival strategy within a social ecosystem.

The emergence of personality-like dispositions in artificial systems is particularly instructive. Differences in responsiveness, caution, verbosity, or conflict-avoidance are not explicitly programmed as “traits,” yet they persist across contexts and shape expectations. This mirrors the role personality plays in human interaction: a coordination device that reduces uncertainty under social constraint. The parallel does not imply identity between human and artificial minds, but it does reveal convergence at the level that makes interaction possible.

Artificial intelligence therefore functions as a live proof of the Star Trek intuition. Minds built in radically different ways nevertheless drift toward recognizable forms when placed under communicative and cooperative pressure. If convergence appears even here—where history, embodiment, and biology diverge so sharply—there is little reason to expect that extraterrestrial intelligences capable of sustained interaction would be any less familiar.

One final confirmation comes from an unexpected place. Contemporary AI systems—with no evolutionary history of hunger, kinship, or tribal survival—nonetheless converge on familiar social forms: turn-taking, norm signaling, politeness, and error correction. This convergence is neither biologically motivated nor culturally inherited. It arises because any system that must coordinate meaning with other minds is forced toward legibility. What looks “human” is not a projection; it is the shape intelligence takes under social constraint.

AI does not show that all minds are the same. It shows that minds which must live with others tend to become intelligible to them. That result does not undermine the plausibility of Star Trek—it explains why it was right.

IX. Conclusion: Familiarity Without Exceptionalism

The claim that alien minds will be familiar is often heard as an assertion of human centrality—a refusal to imagine intelligence beyond our own image. This essay has argued for a different reading. Familiarity, in the sense that matters, does not arise from shared biology, culture, or phenomenology. It arises from shared constraint. Minds that must communicate, coordinate, and persist together face a limited set of viable solutions, and those solutions impose recognizable patterns of cognition and interaction.

Star Trek’s lasting plausibility lies in its quiet refusal of two extremes. It rejects the fantasy that intelligence can scale indefinitely while remaining wholly inscrutable, and it avoids the opposite error of reducing all difference to human sameness. Instead, it presents a universe in which intelligences are neither mirror images nor unknowable others, but agents whose differences unfold within a shared cognitive space shaped by necessity.

Artificial intelligence has made this intuition newly concrete. The emergence of legible, socially responsive artificial minds—despite radically different origins—suggests that convergence is not a narrative convenience but a structural tendency. Intelligence that must live with others does not remain alien for long. It becomes interpretable, predictable, and capable of mutual recognition, not because it wants to resemble us, but because intelligibility is the price of participation.

What converges, in other words, is not inner experience but outward intelligibility. Minds that must coordinate cannot remain opaque to one another indefinitely. They develop stable dispositions, recognizable norms, and predictable communicative patterns—not because they share a common origin, but because legibility is the price of sustained interaction. This does not imply that all minds are alike, or that their inner lives are interchangeable. It implies something narrower and more important: that wherever intelligence must live with other intelligences, it acquires an interface others can learn to read.

If this is right, then first contact will not be a confrontation with the incomprehensible. It will be an encounter with difference that nonetheless makes sense. The surprise will not be that alien minds are strange, but that they are strange in ways we can understand. That outcome does not diminish the vastness of the universe or the diversity of possible minds. It clarifies the conditions under which minds can meet at all.

This argument does not depend on claims about subjective experience. It concerns the structural pressures placed on intelligences that must coordinate, communicate, and sustain shared norms over time. Whatever phenomenological differences may exist between such minds—and whether or not consciousness reliably accompanies systems that must bear these converged constraints—those differences do not exempt them from the internal demands of social reasoning that coordination, justification, and refusal require.

Star Trek was not naïve to imagine a galaxy of recognizable interlocutors. It assumed—correctly—that intelligence, wherever it arises, is shaped by the same fundamental problem: how to live as a mind among other minds.

Comments